All over Fukushima Prefecture, a decade after 3.11, you see the scattered traces of a disaster too overwhelming to contemplate as a whole. There are the sentinel meters still recording levels of ambient radiation, the proliferating tanks of contaminated water at the site itself, the fenced-off areas of the exclusion zone, the abandoned rows of emergency housing, the heaped bags of irradiated soil sitting in front yards and open fields—and even a dwindling herd of nuclear cattle kept alive by farmers out of compassion for these mute witnesses. Something terrible happened here, but how can any art—especially photography, with its penchant for focus—capture its immensity with exactitude?

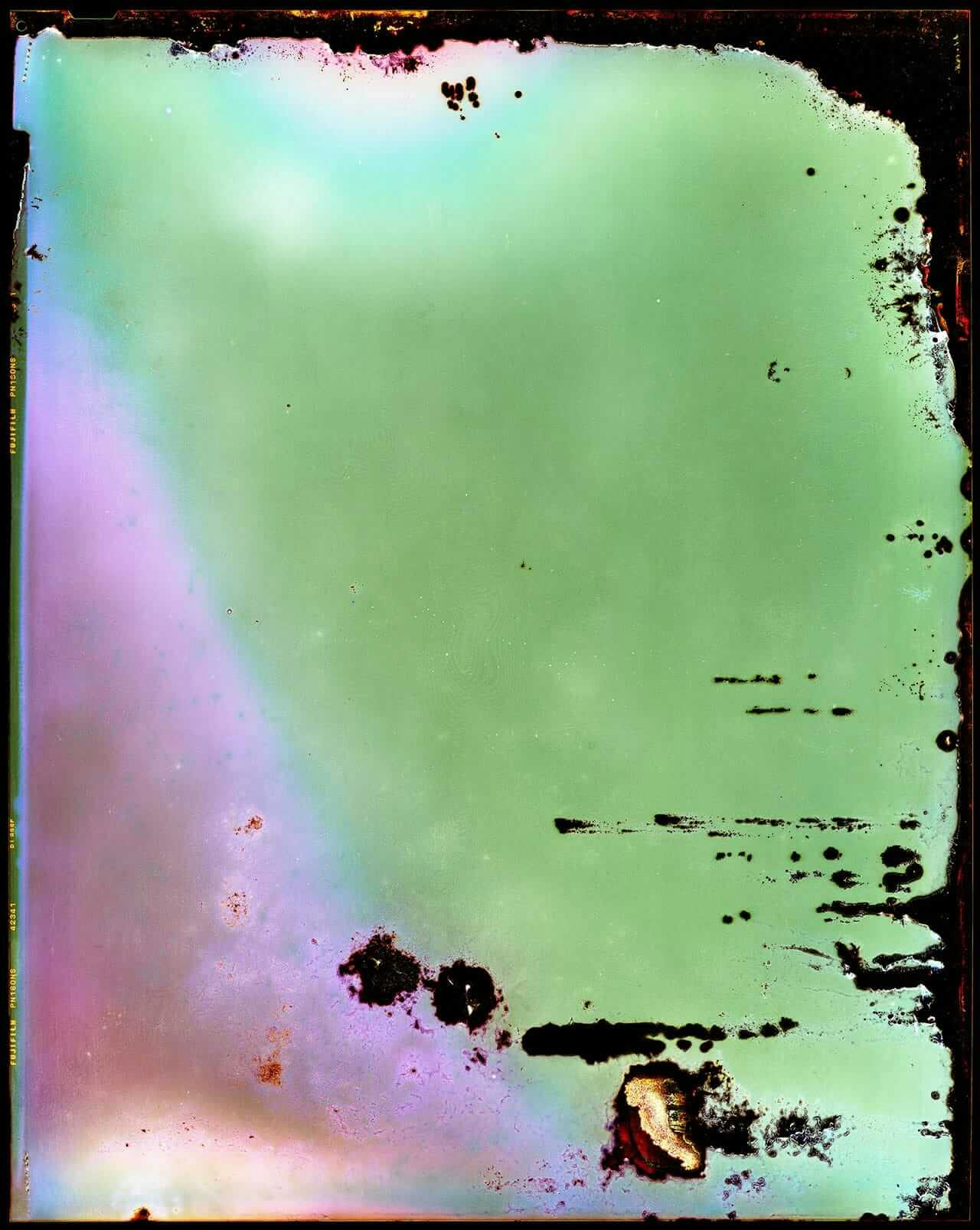

Kawakubo’s “radiance” series forsakes the mundane reminders of tragedy and instead seeks connection to the atom’s secret, seductive core. Developed from unexposed silver halide film buried for months under radioactive soil in Fukushima’s evacuation zone, his images achieve an otherworldly colouration that mirrors the seductions of the nuclear age. The series takes its name from a line of the Hindu religious text, the Bhagavad Gita, which came unbidden to the American physicist Robert Oppenheimer when he watched the first atomic bomb explode in the desert of New Mexico. That blinding light brought an awakening that the atomic physicists of Los Alamos had not calculated in advance. Modern Prometheans, they had gifted humans with a superhuman weapon capable of annihilating the species. Many sought to expiate that sin of hubris by advocating for nuclear power, thereby placating the world with “atoms for peace.”

In the aftermath of the Great East Earthquake, people have wondered how Japan, the only nation to have suffered the devastating effects of atomic bombs, so readily bought into the promises of nuclear power. Did they forget its risks, its death-dealing potential? Were they misled by a corporate-industrial state intent on rehabilitating itself after a humiliating military defeat? Did the threat of lifetimes of contamination mean nothing to the inheritors of Hiroshima’s scorched and barren earth?

Kawakubo’s series gives an unsettling answer, reminding us that danger and the sublime often march hand in hand. Taking us into radiation’s hidden heart, he meditates on the human fascination with forbidden knowledge, the divine sunrise of what he has called the “New Clear Age.” This, after all, is how hellfire might burn: in Milton’s words from Paradise Lost, “No light, but rather darkness visible.”