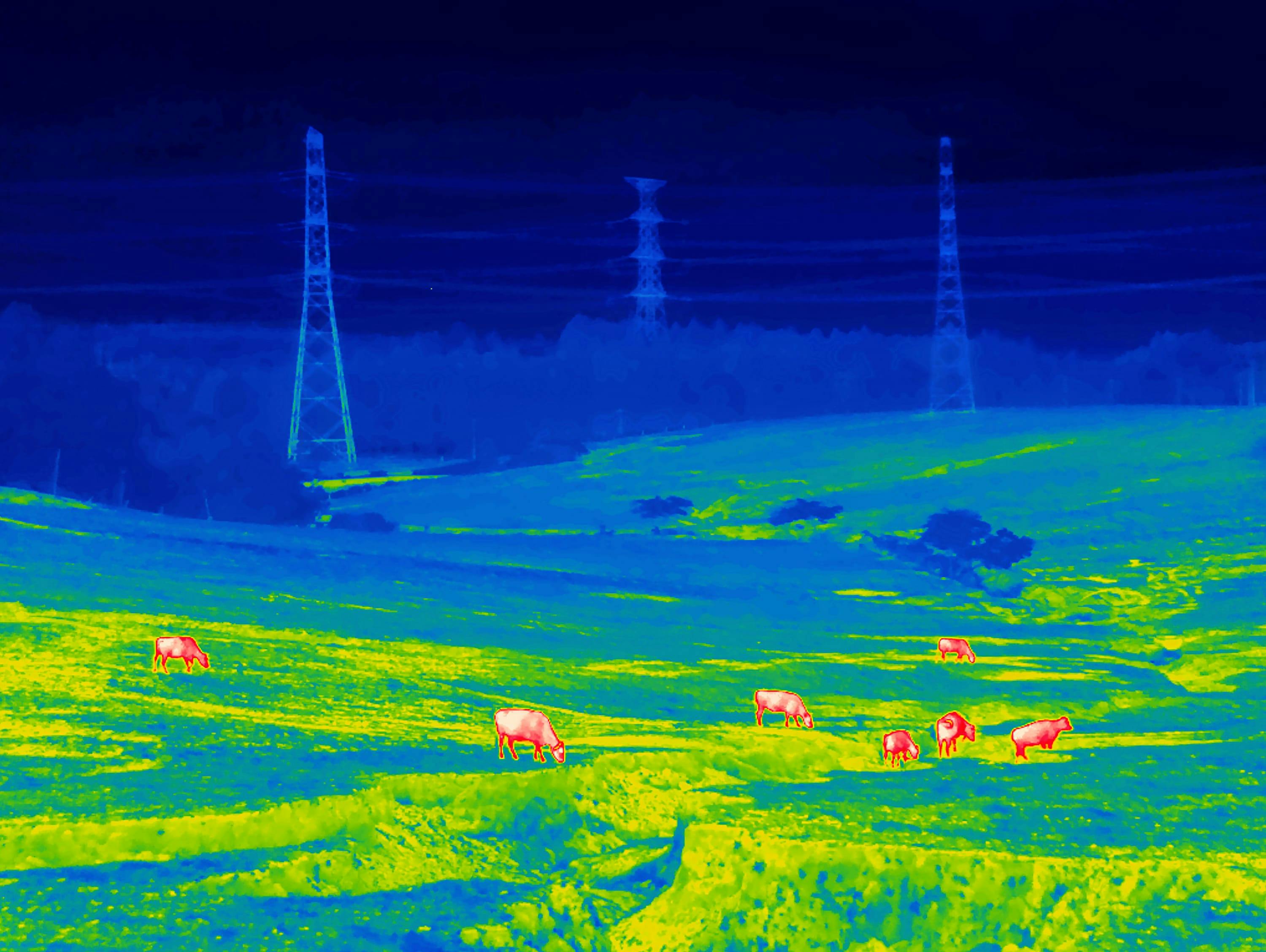

In this striking photo by Giles Price, the warm bodies of cattle pop against the neon yellow-and-green pasture and the cold, dark backdrop of blue layers, like the deep sea, where transmission towers eerily stand. Using thermal technology and showing an aspect of the mundane scenery usually unseeable to human eyes, Price invites viewers to wonder what else may lurk behind what we see.

After the Fukushima nuclear disaster, radiation and its health implications have cast long shadows over the region, not only causing much anxiety but also dividing the residents. Some worry about the long-term health effects, especially on children, while others consider the damage manageable and “radiophobia” more problematic for creating unnecessary stress and stigmatising the region and people. Many of the images in Price’s series of intriguing thermal photos depict people in once-heavily radiated towns where evacuation orders have been lifted. Their body heat in red and orange “radiates” as if it represents their psychological strain and anxiety—uncertainty about their health and about the future of their communities.

In contrast, this photo’s beef cattle peacefully graze at the Ranch of Hope in Namie, 14 kilometres from the power plant that had meltdowns. Against the government order to slaughter them, a rebel farmer has been tending them, not for sale, but as worthy lives not to be meaninglessly killed. The cattle may not worry about radiation, but they have constantly consumed radioactive materials. Their bodies are living evidence of what radiation does to organisms, and a reminder that countless domestic animals were slaughtered or left—often shackled—to starve to death when radiation made the area an exclusion zone.

The invisibility of radiation has long complicated how we address it. Many regard radiophobia as Fukushima’s most urgent problem, but the history of nuclear technology has been full of assorted endeavours to downplay, trivialise, and erase radiation’s harms on people and the environment. Furthermore, radiation protection standards have long relied on studies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki survivors. These studies are well known for their origin in American nuclear strategies and for their various limitations, including a lack of systematic investigation into the effects of internal exposure to radiation—the kind that these cattle have been subject to and Fukushima residents have worried about. Thus, calling people’s worries about the uncertain effects of radiation “radiophobia” or blaming them for fuhyo higai (“damage from unsubstantiated rumours”) belittles their legitimate concerns and elides accountability for the disaster. Historians and social scientists have shown how it became a playbook post-accident response for nuclear institutions and authorities to highlight damage from evacuation and radiophobia, rather than ongoing radiation harms. And it has been tremendously damaging for residents to have their symptoms denied and their concerns, experience, and wisdom trivialised. A lack of new knowledge also helps obscure harms and responsibility: these “nuclear cattle” initially attracted the interest of scientists, but this interest has gradually diminished. Historically, much possible research on survivors, residents, and workers that could have been done has not materialised, allowing older studies to dictate radiation protection; studies on childhood and adolescent thyroid cancer in Fukushima have consistently faced efforts to end them.

Price’s photograph beckons us to remember the disaster and reflect on what is beneath the surface. Besides radiation, the enduring struggles and sufferings of Fukushima residents, A-bomb survivors, and other victims of radiation injuries worldwide (from mining, nuclear tests, accidents, facilities, waste, and clean-up) remain unseen in plain sight. These voiceless yet flashy red cattle are part of the same history that has produced, and ignored, numerous global hibakusha (“exposed peoples”).